Genius in Hindsight: TypeScript Type Annotations

Log InSearch Resources

Popular Posts

Aug 19 2024

Microsoft Fabric reference architecture

Aug 15 2024

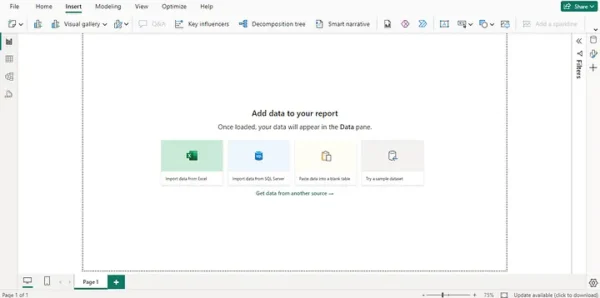

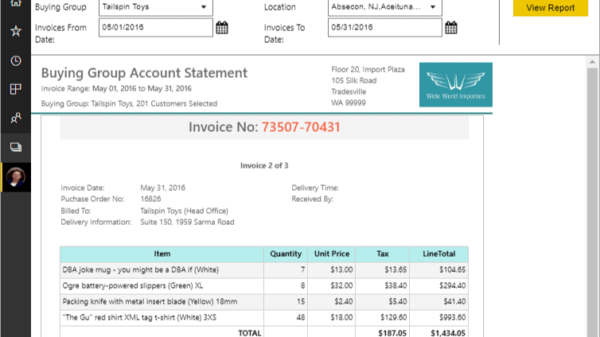

Business Intelligence with Power BI

Aug 19 2024

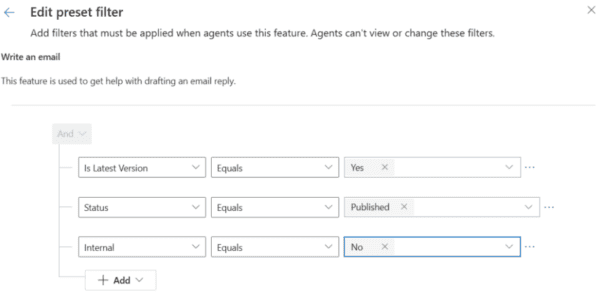

Copilot – Filters